THE ALAMO – The Rebuilding Of A Legend

Words: Uma Basso

Words: Uma Basso

Photos: 400tmax, Richard McMillin, SeanPavonePhoto, skodonnell

Famously known as a symbol of resistance, the Alamo is a historic landmark in San Antonio, Texas. First constructed as a mission in the early 18th century, this legendary building became the site of the Battle of the Alamo, whereby hundreds of Texans gave up their lives to resist the Mexican Army.

For the last two centuries, the Alamo has been a target of controversy. While the Alamo suffered extreme destruction during the war, much of the damage it faced over time resulted from disputes. Arguments over its meaning and purpose have caused further destruction of this American milestone. Many times, rebuilding projects were abandoned, leaving the Alamo in partial ruins throughout its life.

Poor maintenance and erosion have taken a toll on these historic buildings. Coupled with the erratic placement of stores, homes, and roads throughout the complex over the last hundred years, the beauty of the Alamo has been drowned out by the center's noise and an array of commercial buildings.

Still, this legendary site attracts an estimated three million people who flock to the site for a glimpse of American spirit and perseverance. To recapture the sentiment of independence and resistance that the Alamo was once known for, San Antonio's city has engaged in an exciting restoration project to tell the story of the Alamo.

HISTORY

The site known as the Alamo was once a chapel of the Mission San Antonio del Valero was founded by the Franciscans sometime between 1716 and 1718. After its eventual abandonment near the end of the 17th century, the Spanish periodically occupied the partially ruined site. Set in a grove of cottonwood trees, this complex was dubbed the Alamo, which means "cottonwood," by the Spanish armies. When Mexico gained its independence from Spain, their soldiers frequently occupied the site.

The Alamo is the site of the historic battle that launched the Texas Revolution back in December 1835. A group of less than 200 Texan volunteers drove the Mexican Army from San Antonio. Thinking the conflict was over, the volunteers remained at the Alamo. Fighting erupted again on February 23, 1836. Known as the Battle of the Alamo, this small group of volunteers was vastly outnumbered but held back the Mexican forces until they were eventually overrun on March 6, 1836.

Even though the revolutionaries suffered defeat at the Alamo, the siege soon became a symbol of perseverance and resistance. During the later Mexican American War of 1846-1848, the phrase “remember the Alamo” became the battle cry of U.S. soldiers.

ORIGINAL CONSTRUCTION

The structure that eventually became known as the Alamo started as a chapel. Built by the Spanish, it was used as a fortress for American Indians who had converted to Christianity. After years of temporary shelters, construction of the permanent building started in 1744. The first structure was made of limestone, mud, and wood; however, the church and tower collapsed in the late 1750s.

The reconstruction of the Alamo began in 1758. The planned structure was three stories tall, with a dome on top and two bell towers on either side. The first two levels of the building were using 4-foot-thick blocks of limestone. The interior walls had niches to hold statues and carvings around the doors. There were four stone arches constructed for the eventual dome. However, the Alamo's third floor, dome, and bell towers were never completed. Around the compound, approximately 30 buildings were constructed of adobe and mud and used as homes, workstations, and storage.

The Spanish eventually took over the buildings. Beyond lodging, the structure was later modified to be used as a hospital and to house prisoners. After Mexico gained their independence from Spain, the compound was used by the Mexican military. The large pillars intended to hold the dome ceiling were knocked down. The stone was repurposed to build a ramp leading up the unfinished third floor, which was used to fire cannonballs against the Texans.

POST-WAR ALAMO

At the end of the Texas Revolution, the Alamo was left in ruins. Mexican soldiers had knocked down walls and set fires throughout the complex. In 1846, the U.S. Army began its reconstruction, rebuilding the walls with the original stone lying around the compound. The soldiers added a wooden roof, new windows, and a bell-shaped façade to the chapel. The new complex had offices, stables, storage facilities, and a supply depot. A two-story building was constructed. This building, along with its repurposed convent, as a grocery store. Eventually, the Catholic Church sold the chapel to the State of Texas.

Visitors flocked to the Alamo to catch a glimpse of this gritty American landmark. Yet, many were disappointed with what they saw. The area was heavily commercialized with stores, hotels, and restaurants, while the Alamo was in terrible shape. The walls were damaged and loaded with graffiti. Interior statutes were missing or destroyed.

In 1892, the Daughters of the Republic of Texas (DRT) formed with the intent to preserve the Alamo. The key members of the DRT, Adina De Zavala and Clara Driscoll raised and donated $75,000 to purchase the convent in an effort to restore it.

Yet like much of the Alamo’s history, both members were at odds with its restoration, with De Zavala wishing to restore the convent and Driscoll wanting to tear it down and replace it with a monument and plaza. After a lengthy dispute and Driscoll forming a competing DRT chapter, a judge ruled that Driscoll's group were the Alamo's official custodians.

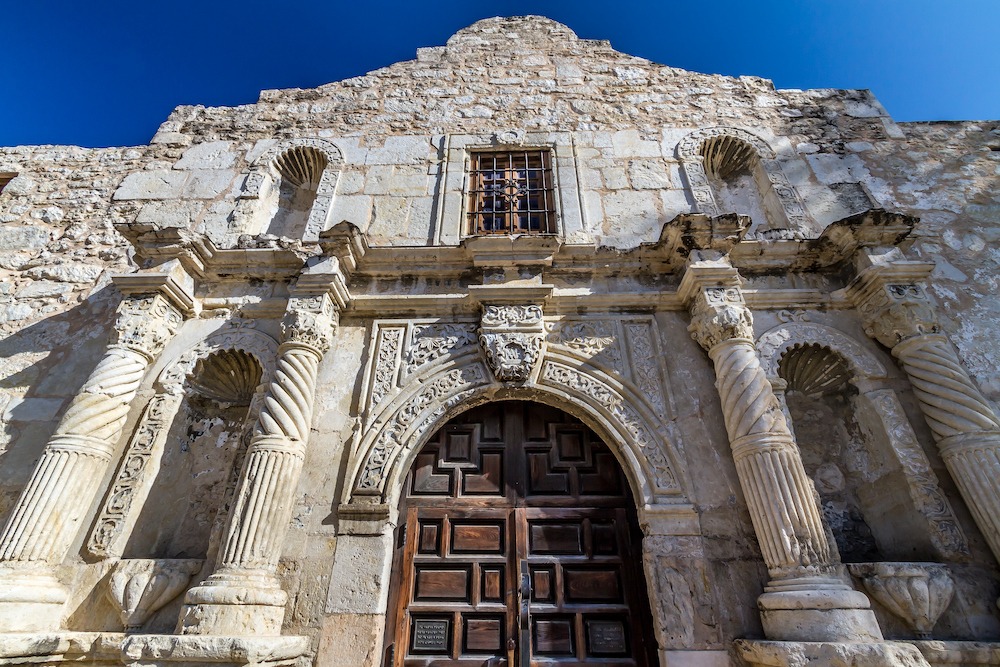

Unusual Perspective of the Historic Spanish Mission and Texas Fort, The Alamo, San Antonio, Texas.

Unusual Perspective of the Historic Spanish Mission and Texas Fort, The Alamo, San Antonio, Texas.

Yet, in another turn, the incoming governor decided in 1910 to remove the DRT as official custodians and, instead, authorized the restoration of the convent. Fitting for the Alamo's history, the $5,000 allocated for its restoration was not enough to complete the project, so the convent remained unfinished. The controversy continued with the lieutenant governor authorizing the removal of the second story walls of the convent.

In the years that follow, disagreement plagued the site of the Alamo. Some felt it should be restored to honor its missionary roots. For others, it should be revered as a symbol of resistance. Suffice to stay, no consistent plan to restore the landmark was in place. Instead, restoration became a series of short-term fixes with no central purpose. The plaza upon which the Alamo sat continued to become saturated with stores and restaurants. Visitors would find historic landmarks scattered between a slew of commercial properties.

ENVIRONMENTAL FACTORS

Not only did prolonged disagreements and poor maintenance impact the Alamo, but the structure is also highly susceptible to erosion. The building was constructed from limestone taken from the San Antonio River. Limestone is vulnerable to environmental factors, like heat and cold. As temperatures change, the limestone expands and contracts, losing pieces throughout the process. These extreme changes have taken a toll on the Alamo’s structure.

The changing use of the Alamo and its surroundings may also have contributed to its erosion. The installation of air conditioning units back in the 1960s may have further degraded its limestone walls. With the Alamo located in San Antonio's center, many people suspect that car noise and fumes have played a role in the structure’s erosion.

A NEW PLAN

After several years of discussion and negotiation, plans are now underway to tell the story of the Alamo. In 2018, the San Antonino City Council approved the plans to redesign this landmark. According to San Antonio Mayor Ron Nirenberg, “To truly tell the story of the Alamo, we must tell the entire story of the Alamo, from its establishment as a mission to the battle itself and its place as a civic gathering venue and memorial.”

The $450 million project pays tribute to the Alamo’s storied past. The goal is to revive the location's original footprint to resemble how it appeared during the 1836 battle. The complex would have a cohesive design with its landmark buildings, creating spaces to speak into its history. Visitors are greeted by Cenotaph, the memorial constructed in 1936 to honor the Texas soldiers who gave their lives to defend their country 100 years prior. The project calls for the deteriorating Cenotaph to be restored and moved near the entryway.

The plaza features an open-air museum, which shows historical events where they happened. Calvary positions, Native American burial grounds, and the main gate are points along the way in this renovated project.

A High Dynamic Range shot of the historic Alamo early in the morning after a storm.

A High Dynamic Range shot of the historic Alamo early in the morning after a storm.

The plan calls for the restoration of often-disputed Church and Long Barracks. The Crockett, Palace, and Woolworth buildings are to be repurposed as a museum and visitor center. Traffic is to be re-routed, opening space for walking paths, gardens, and common areas for people to enjoy. The plan calls for droves of shade trees to be planted throughout the plaza to enhance the original spatial volume of the Mission.

Like much of the Alamo's life, the restoration plans are not without controversy. The original plan calls for moving the Cenotaph to the plaza entrance to honor the sacrifice of the Texas forces and start the visitor journey. But this has met much resistance, with the relocation recently voted down by the Texas Land Commission in September 2020 and many citizens divided on where this legendary symbol should stand.

With the Cenotaph move marked as the first phase of the plan, this has dealt a blow to the project, which had a targeted completion date of 2024, just in time to celebrate the Alamo's 300th anniversary's first construction. For many, the move by the Commission is disappointing and may have placed the project in jeopardy.

Yet, for others, the project's implementation was doomed from the start. However, this setback presents an opportunity to go back to the drawing board and rethink the project’s ultimate purpose and how to best carry it out. While controversy continues to plague the Alamo, it may soon get to tell its story.