Marvelous Masonry: Theaters of the Ancient World

Words: Scott Conwell

Words and Photos: Scott Conwell, FAIA, FCSI, Director of Industry Development, International Masonry Institute

Introduction

Since ancient times, the entertainment complex has been a celebrated building type. Among every major city’s magnificent churches and government buildings were its monumental arenas and theaters. The influence of a city was proportional to the seating capacity of its largest arena, where a community would gather to cheer on sporting events, dramas, concerts, and executions.

I became intentional about visiting and documenting these impressive gathering places in my travels abroad in the past ten years or so, and I thought it would make a good study to examine some of these historic masonry structures, all constructed or renovated during the Roman Empire. I will look at these buildings through the lens of their architecture, their construction, and their historic significance, with original photography and a few personal reflections peppered in.

This article will examine five notable arenas:

- Flavian Amphitheater, Rome, Italy

- Verona Arena, Italy

- Odeon of Great Theater of Herodes Atticus, Athens, Greece

- Roman Theater of Hierapolis, modern-day Turkey

- Theaters of Laodicea, modern-day Turkey

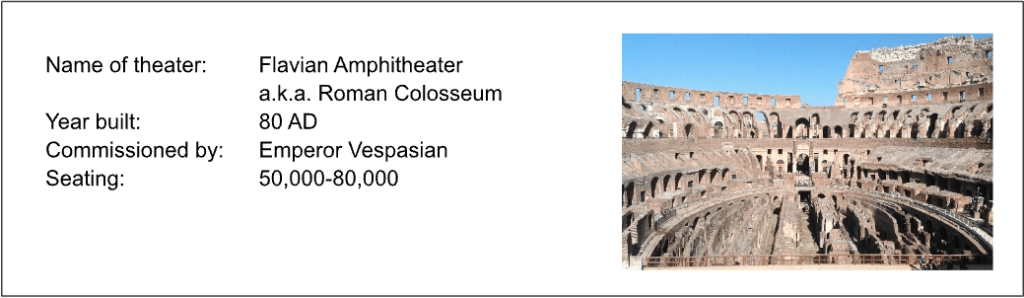

1. The Flavian Amphitheater, Rome

The Flavian Amphitheater in Rome, also known simply as the Colosseum, is the archetype of Roman theaters. Its three soaring levels of brick and stone masonry with 80 arches per level make this structure one of the most recognized and enduring examples of masonry.

Construction of the Colosseum began around 72 AD under the emperor Vespasian. It was built to exhibit gladiator combats, animal slayings, and public executions. Construction was completed in approximately 80 AD. The stadium’s maximum seating capacity was about 80,000 (Figures 1.1 and 1.2). The dimensions are roughly 620 feet x 513 feet x 147 feet high.

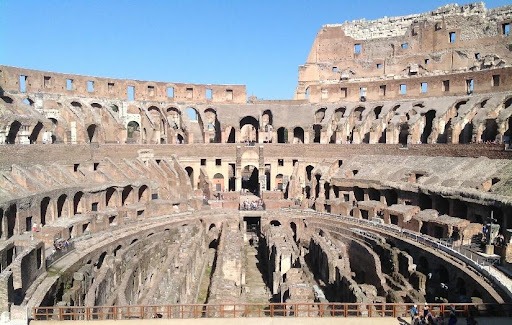

Masonry materials used for the structure include travertine stone, volcanic stone, brick, and an early form of concrete known as Roman concrete (Figure 1.3). About 100,000 cubic meters of travertine mined at the quarries of Tivoli, 20 miles away, were used in the Colosseum, held together by thousands of iron cramps. Roman concrete consisted of small stones suspended in a binder of fine volcanic ash, lime, and water. Behind the travertine cladding, the walls comprise multiple wythes of clay brick.

In addition to being a marvel of masonry construction, the Colosseum is a paragon of efficient circulation, as any assembly space must be. The building was designed with 80 entrances (Figure 1.4). In a matter of minutes, entire audiences could exit the structure through the vomitorium (from the Latin root vomere, meaning “to spew forth”), the wide passage between the seats and the exits.

On a personal note, I visited the Colosseum with my wife, Raquel, in 2012. This was our first trip to Italy, and kind of a big deal for us to leave our three pre-teen kids back home with their grandparents. We had an amazing time taking in the architecture, the wine, and the sights of Rome and Florence, and we would return to Italy on future vacations.

Fig. 1.1. The Colosseum had a seating capacity for 50,000-80,000 at various points in history.

Fig. 1.2. The Colosseum was built to exhibit gladiator combats, animal slayings, and public executions.

Fig. 1.3. Roman concrete on top of the brickwork.

Fig. 1.4. The Colosseum originally had 80 semicircular arches on each of 3 levels.

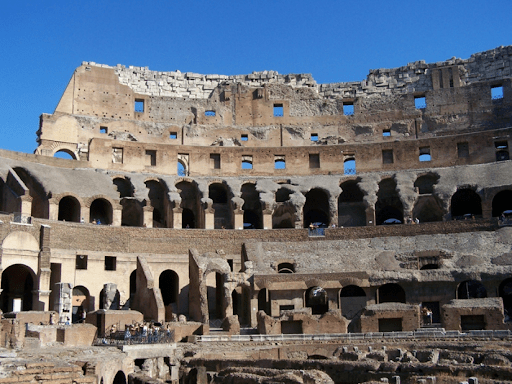

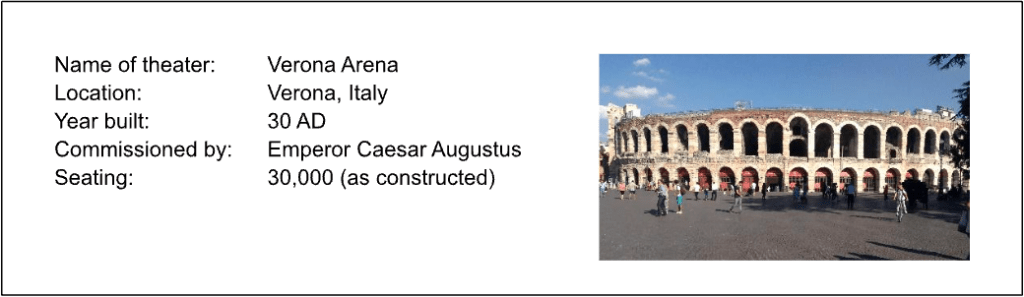

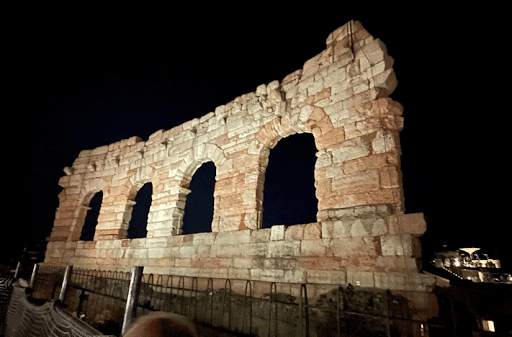

2. The Verona Arena, Verona, Italy

Predating the Roman Colosseum and still hosting performances today, the Arena in Verona, Italy, is a masterpiece of stone masonry. This gathering place was constructed in 30 AD under Emperor Augustus. It was built with white and pink marble (Figure 2.1) from the nearby Valpolicella region of northern Italy, and it had a seating capacity of about 30,000 (Figure 2.2).

The Arena’s dimensions were originally approximately 100 ft. x 406 ft. x 100 ft. high. However, an earthquake in 1117 destroyed much of the structure's outer ring. The stone was reclaimed to build many other buildings in the city. A portion of the outer wing, known as the Ala (Figures 2.3 and 2.4), survived the earthquake, and is intact to this day. This remaining high portion of the Ala comprises 4 arches on 3 orders decorated with Tuscan-style buttresses and cornices.

On a personal note, I visited the Verona Arena for the first time in 2014 as part of an architectural program called Stone Academy held in conjunction with Marmomac, the large international stone conference. I remember noting how the Arena was the focal point of the city center, anchoring the Piazza Bra (Figure 2.5) with its many cafes and shops all around and large crowds of people at all hours of the day and night. I visited Marmomac again two years later, this time as part of the presentation team, where we made another visit to the Arena.

So enamored was I with the structure and the city; this is where I brought Raquel in 2022 (Figure 2.6) to celebrate our 25th wedding anniversary. We had tickets to attend the opening night of the opera Carmen, and as luck would have it, our seats were near my favorite high-arched walls of the Ala! The show started at twilight, around 9 pm, but sitting on the stone seats that had absorbed the long day’s store of summer heat was a lesson in masonry’s effective thermal mass. Warm stone seats notwithstanding, the Arena is beautiful and a great venue for attending events even today.

Fig. 2.1. The arena was built with white and pink marble from the Valpolicella region of northern Italy.

Fig. 2.2. The arena had a seating capacity of 30,000.

Fig. 2.3. A 3-level high portion of the outer wing, known as the Ala, survived the earthquake of 1117 and remains the signature element of the Verona Arena.

Fig. 2.4. The stone Ala as viewed from the inside of the arena.

Fig. 2.5. The arena anchors the Piazza Bra in Verona’s city center.

Fig. 2.6. The author and his wife visited the arena on in 2022.

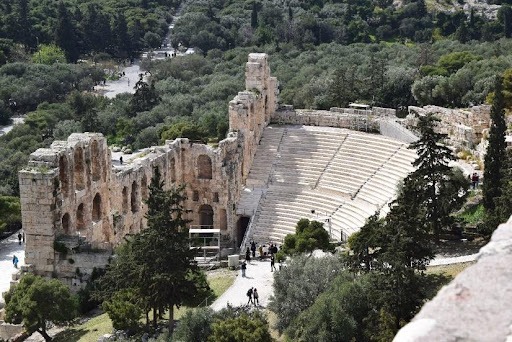

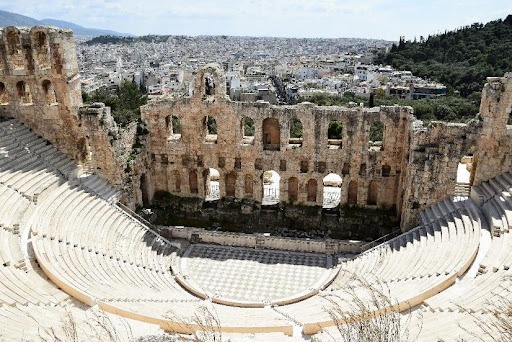

3. Odeon of the Great Theater of Herodes Atticus, Athens, Greece

Built on the southwestern slope of the Acropolis in Athens (Figures 3.1 and 3.2), the Odeon of Herodes Atticus, or simply the “Herodeon,” is one of the oldest and most prestigious theatres in the world.

The Herodeon was built in 161 AD by the Roman Senator Herodes Atticus in honor of his wife, Aspasia Annia Regilla. It has a seating capacity of about 5,000 (Figure 3.3). The theater comprises a steep-sloped structure with a three-story stone front wall (Figure 3.4), and it originally had a roof constructed of cedar. It was built to host dramas, musical performances, and community gatherings. The original Herodeon was destroyed by an East Germanic sect called the Heruli in 267 AD and left in ruins. It was rebuilt with much of the original stone in the 1950s (Figure 3.5) and has served as a concert venue in modern times.

On a personal note, I visited Athens in 2019 and spent nearly an entire day at the Acropolis, an experience I will never forget. Since I was traveling by myself, I was able to take my time viewing all the temples and monuments. When I was there, the inside of the Herodeon was closed to tourists, but the top of the Acropolis offered spectacular views of the seating and the stone facade backdrop. The Parthenon may be the top tourist attraction on the Acropolis, but looking down at the Odeon was every bit as spectacular.

Fig. 3.1. View of the Herodeon from the top of the Acropolis.

Fig. 3.2. The Herodeon is a steep-sloped structure with a 3-story stone facade.

Fig. 3.3. The Herodeon had a seating capacity of about 5,000.

Fig. 3.4. View of the Herodeon’s stone front wall. The author visited in 2019.

Fig. 3.5. Pentelic marble was used for the building’s restoration.

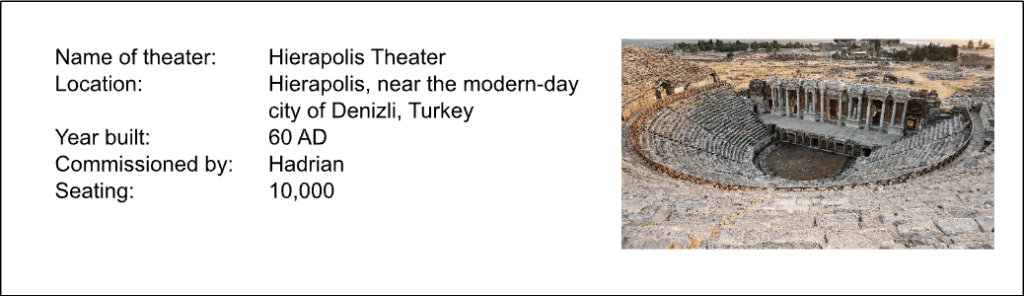

4. Roman Theater of Hierapolis, modern-day Turkey

Carved into the hills surrounding the ancient city of Hierapolis (Figure 4.1), this great Roman Theater is one of many notable buildings at the Hierapolis Archaeological Site in modern-day Turkey (Figure 4.2). Its stunning architecture, friezes, and location make it one of the best-preserved theaters in the region. At its peak, it had a seating capacity of about 10,000.

The Roman Theater of Hierapolis was constructed in the second century AD under the reign of Emperor Hadrian when Hierapolis became part of the Roman province of Asia. The theater was likely part of an extensive rebuilding period following a devastating earthquake in 60 AD. Hadrian is known to have visited Hierapolis in 129 AD.

The original facade was about 300 feet long, and the full extent remains today, though largely restored and rebuilt. In the 3rd century, the stage was enlarged, and the lower seating area was rebuilt. In the 4th century, the theater was restored and renovated to enable it to hold water exhibitions and games. At this time, the facade was modified and decorated with elaborate limestone and marble carvings.

As it stands today, the theater’s exterior is relatively unassuming, but the interior contains one of Anatolia's most complete and best-preserved collections of Greco-Roman ornament (Figures 4.3 and 4.4). The current stage is mostly the original stone pieced together with modern stabilizers and replicas of the original sculptures, which are now preserved in the Hierapolis Archaeology Museum.

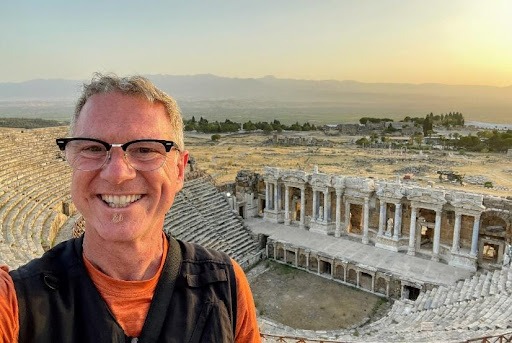

On a personal note, I visited Hierapolis in 2021 (Figure 4.5), taking advantage of a free Saturday after attending the Marble Fair in Izmir, a couple of hours’ drive away. Since I was traveling by myself, I was able to take my time viewing the site, which includes this Roman theater, a vast necropolis, and the tomb and martyrdom site of St. Philip, where he is said to have been crucified in 80 AD. The theater, with its views of the travertine terraces and hot springs of Pamukkale below, was so amazing I returned for a second visit in the evening, taking advantage of my all-day ticket to the archeological site.

Hierapolis draws tourists by the busload, but mostly for its natural features, namely the aquamarine travertine pools. So, when I visited, the theater site was quiet and peaceful, providing an ideal place to sit in solitude on a centuries-old stone bench and imagine what it must have been like to attend a Roman spectacle.

Fig. 4.1. Overview of the 10,000-seat Roman Theater of Hierapolis with the white travertine terraces of Pamukkale visible on the horizon.

Fig. 4.2. The theater is one of many elements in the vast archeological site of Hierapolis.

Fig. 4.3. Today, the stage is adorned with replicas of the original sculptures which are now preserved in the Hierapolis Archaeology Museum.

Fig. 4.4. Detail of the seating and the stage.

Fig. 4.5. The author visited the Hierapolis in 2021.

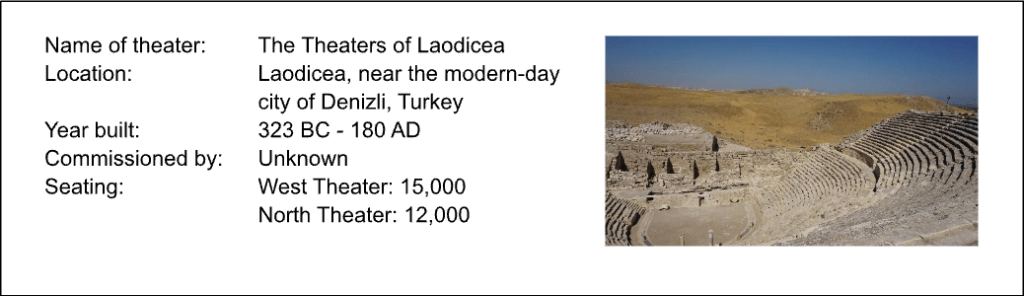

5. Theaters of Laodicea, modern-day Turkey

Not far from Hierapolis in modern-day Turkey lie the ruins of the ancient city of Laodicea. Both communities figured prominently in the history of Western civilization, from the Greeks to the Romans to the Byzantines to the Ottomans. The architecture in these important cities was of the highest order, built to honor deities, men, and God. Both cities have well-preserved and restored masonry and tile relics, and both figure prominently in the New Testament of the Bible. Laodicea has not one but two theaters that can be seen today.

The theaters in Laodicea are known today as the North Theater (Figure 5.1) and the West Theater (Figure 5.2). Each was built into the slope of a hill in the Hellenistic period, between the death of the Macedonian king Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the rise of Augustus in Rome in 31 BC. The West Theater is older than the North Theater but larger and better preserved, having recently been restored (Figure 5.3).

Laodicea’s North Theater was used until the early 7th century and had a seating capacity of about 12,000. The names of wealthy families and civic associations were engraved on many of the seats to mark their reserved spaces. The West Theater had seating for about 15,000.

In the years of the Roman Republic, Laodicea benefited from its location on a major trade route, and it became one of the most important commercial centers of Asia Minor and a seat of the early Christian church. St. Paul addresses the Church in Laodicea in his epistle to the Colossians and in his first letter to Timothy. Notably, the city was home to one of the seven churches of Asia addressed by St. John in the book of Revelation.

On a personal note, I visited the Archeological Site of Laodicea in 2021, the day after I visited Hierapolis. Both sites are in ruins but are undergoing excavation and are in various stages of restoration. Whereas the hot springs and travertine terraces of Hierapolis are a tourist draw, Laodicea was desolate, making for a peaceful and contemplative visit. From atop the West Theater, I could see the travertine terraces of Pamukkale in the distance (Figure 5.4).

Fig. 5.1. The north theater of Laodicea built into the slope of a hill had a seating capacity of about 12,000. It is currently in ruins.

Fig. 5.2. The west theater of Laodicea had a seating capacity of about 15,000. It is currently undergoing restoration.

Fig. 5.3. Detail of the west theater’s stage building and stone seating.

Fig. 5.4. The white travertine terraces of Pamukkale are visible in the distance in this view overlooking the north theater of Laodicea.

Conclusion

Our history is a history of civilizations. Civilizations are defined by the communities that make them up, and community life is shaped by its buildings. Public gathering places have forever anchored the communities they serve. When we today visit the arenas and gathering places of the Roman Empire today, we gain a glimpse into the community life of antiquity. Such insights are only available to us because these structures were built with solid and lasting materials. Will we leave the same legacy for our descendants? With masonry, we can.